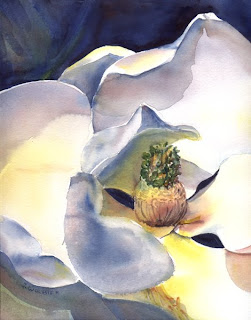

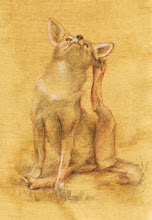

Wet glazing is an exciting watercolor technique. This technique is used for painting sunrises and sunsets and, although it is very difficult to control, can produce wonderful effects. The images that you see above are two ways to paint with wet glazes. Believe it or not, both paintings are painted with the same three colors: cadmium yellow light, permanent alizarin crimson, and colbalt blue. This includes not only the skies, but also the surf, the birds, and the landscape details.

In the top painting, the glazes were applied in thin layers. In the bottom painting, they were applied with varying intensity in different areas. To get the wet glazing effect in the top painting, start with the cadmium yellow light. Mix lots of water into the paints. On dry paper, apply a thin layer of the yellow evenly over the whole paper. Let it sit for a minute or two, then apply a thin layer of the permanent alizarin crimson. Let that glaze sit for a minute or two and then apply the cobalt blue layer. It may not look great while it is still wet, but when the pigments separate out of the binder and drop into the paper crevasses, the painting starts to glow.

To paint the bottom painting, start with the cadmium yellow light and apply it in various thicknesses on parts of the paper. You can paint a graded wash from the top or the bottom. Here I put lots of yellow right in the middle and graded it up and down. Then apply the permanent alizarin crimson, again in thicker and thinner paint in graded washes around and over the yellow. The final layer is the cobalt blue, again applied in various thick and thin layers on only parts of the painting.

Once the background wet glazing has been painted, you can start adding in details. This can be done while the glazes are still wet by lifting or adding darker paint. Or you can wait until the painting has dried. It is a wonderful technique, but let me warn you, it is almost impossible to truly predict what you will get once it dries!